Cyber Security: A Pre-War Reality Check

Posted on May 14 2024

This is a lightly edited transcript of my presentation today at the ACCSS/NCSC/Surf seminar ‘Cyber Security and Society’. I want to thank the organizers for inviting me to their conference & giving me a great opportunity to talk about something I worry about a lot. Here are the original [slides with notes](https://berthub.eu/prewar/ncsc accss surf keynote bert hubert-notes.pdf), which may be useful to view together with the text below. In the notes there are also additional URLs that back up the claims I make in what follows.

So, well, thank you so much for showing up.

And I’m terribly sorry that it’s not going to be a happy presentation.

This is also sort of an academic environment, and this is not going to be an academic talk. This is not going to be subtle. But I’m trying to alter, to modulate your opinion on the world of cyber security a little bit.

Cyber security and society, a pre-war reality check

We’re already worried enough about cyber security. Is anyone here not worried about cyber security? And you could go home now, otherwise. Okay, that’s good. So you can all stay.

First, some important words from Donald T:

“I know it sounds devastating, but you have to get used to the fact that a new era has begun. The pre-war era.”

And this comes from Donald Tusk, the Polish Prime Minister from 2007 to 2014.

And at the time, he, and the Baltic states, said that Russia was a real threat. And everyone’s like, yeah, yeah, it’ll last. And we’ll just do so much business with them that we will not get bombed. And that did not work.

And now Donald Tusk is again the Prime Minister of Poland. And he’s again telling us that, look, we are in a bad era and we are underestimating this.

We are used to thinking about cyber security in terms of can we keep our secrets safe? Are we safe against hackers or ransomware or other stuff? But there is also a war dimension to this. And this is what I want to talk about here.

So briefly, Nicole already mentioned it, I’ve done a lot of different things, and this has given me varied insights into security. I’ve worked with Fox-IT for a long while. PowerDNS should not be a well-known company. But it delivered services to KPN, Ziggo, British Telecom, Deutsche Telekom. And they all run their internet through the PowerDNS software.

And through that, I got a lot of exposure to how do you keep a national telecommunications company secure.

And can the national telecommunications companies keep themselves secure?

And that was useful.

I spent time at intelligence agencies, I spent time regulating intelligence agencies. And that may be also useful to talk about a little bit. Through that regulatory body, for nearly two years, I got a very good insight into every cyber operation that the Dutch government did. Or every cyber operation that was done on the Dutch government.

I cannot tell you anything about that stuff. But it was really good calibration. You know what kind of stuff is going on. Uniquely to the Netherlands is that this board, which regulates the intelligence agencies, actually has two judges, the little guy on the left and on the right:

And in the middle, there was someone with different experience. That’s what the law says. They couldn’t get themselves to say someone with technical experience. It was a bridge too far. But at least they said we can have someone with different experience.

And this is unique in Europe, that there is an intelligence agency that is being regulated with an actual technical person in there. And we’ll come to why that is important later.

So everyone is of course saying, look, the cyber security world is just terrible and doomed. And someone is going to shut off our electricity and kill our internet and whatever. Or disable a hospital. And so far, not a lot of this stuff has actually been happening.

In 2013, Brenno de Winter wrote a book called The Digital Storm Surge, in which he said, look, we haven’t had any real cyber incidents that really speak to the imagination. So we’ve had, of course, the printer is down. The printer is always down.

We don’t actually rely on computers that much, because they break all the time. So we do not have a lot of life and death situations involving computers.

Brenno, in 2013, predicted that we would only take cyber security seriously once we had the kind of incident where lots of self-driving cars, who can avoid pedestrians, that you flip one bit. And they all start aiming at pedestrians.

And you get like thousands of people dead because all kinds of cars decide to drive over people. And he mentioned there that before the sinking of the Titanic, there was no regulation for how to build ships.

So you could just build a ship and if it looked good, people assumed that it would also be good. And only after the Titanic, they started saying, oh, we need to have steel that’s this thick, and you can have the steam engine, not here, it must be there. So he said the Titanic was the regulatory event for ship building.

And in 2013, Brenno said we have not had anything serious yet, and we will only get serious legislation once the Titanic sinks. And it didn’t sink.

However, the EU got vision.

his is the most optimistic slide in the whole presentation.

For some reason, the EU decided that this couldn’t go on. And so they launched like six or seven new laws to improve the state of our cybersecurity.

And this is like the sinking of the Titanic. So we’re not properly realizing how much work this is going to be. Because the thing is, they’ve written all these laws already, and only one of them is sort of semi-active right now, and the rest is still coming.

So this is our post-Titanic environment, and this might improve the situation of cybersecurity somewhat. Because it’s like terrible.

So some real cyber incidents, real stuff that broke war.

This is the former president of Iran, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. And here he is admiring his uranium ultracentrifuge facilities.

And this was the famous Stuxnet operation, where apparently the West was able to disable the ultracentrifuges used to create highly enriched uranium.

And not only did they disable it, like the factory is down now, it tore itself to shreds physically.

So this is one of the few sort of military cyber attacks that we know about.

This is like one third of them. The other one that happened was just before Russia invaded Ukraine, they managed to disable the Viasat modems. And this is an interesting case. These modems are used for satellite communications. And they were able to attack these modems so that they physically disabled themselves.

It was not like the denial of service attack on the network. No, they managed to wipe the firmware of all these modems in such a way that it could not be replaced.

The reason we know about this stuff so well is it turns out there were lots of windmills that also had these modems.

In Germany, apparently 4,000 of these modems stopped working. And there were 4,000 wind turbines that could no longer be operated. So this was a military cyber attack that happened as Russia was invading Ukraine. And it was of great benefit to them because it disabled a lot of military communications in Ukraine.

But this is the kind of thing that can happen, only that it’s quite rare.

Earlier, Russia disabled a lot of the electricity networks in Ukraine using a similar kind of attack. And it turned out that the Ukrainians were so good (and their systems so simple and robust) that they had a disruption of like only six hours, which is really impressive.

And I want you to imagine already what would happen if we had such an attack on a Dutch power company. They’re very nimble [irony, they are not]. I mean, try asking a question about your invoice.

So I’m going to talk about rough times. And I started my presentation with Donald Tusk telling us we are in a pre-war era, and I truly believe that. But it’s a difficult thing to believe. I also do not want to believe it. I also want to be like, no, this stuff is over there in Ukraine. It’s not here. But even if you think there’s only a 10% chance, then it’s quite good to already think about this kind of stuff.

Even if you are such a diehard pacifist that you are convinced that it’s never going to happen, you can just imagine that I’m talking about robustness in the face of climate change.

Because also then you want to have your stuff that works.

So there are three things I identified, that you really care about in a war, in a chaotic situation where there’s no power.

You want infrastructure that is robust, that does not by itself fall over.

If we look at modern communications tools, like, for example, Microsoft 365, that falls over like one or two days a year without being attacked. It just by itself already falls over. That’s not a robust infrastructure in that sense.

Limited and known dependencies.

Does your stuff need computers working 5,000 kilometers away? Does your stuff need people working on your product 5,000 kilometers away that you might no longer be able to reach?

So, for example, if you have a telecommunications company and it’s full of telecommunications equipment and it’s being maintained from 5,000 kilometers away, if something goes wrong, you better hope that the connection to the people 5,000 kilometers away is still working, because otherwise they cannot help you.

The third one, when things go wrong, you must be able to improvise and fix things. Truly own and understand technology.

For example, you might not have the exact right cable for stuff, and have to put in an unofficial one.

You might have to fix the firmware yourself. You must really know what your infrastructure looks like.

Let’s take a look at these three aspects of modern communications methods. And we’re going to start with one of my very favorite machines, and I hope you will love this machine as much as I do.

This is the sound-powered phone. So a sound-powered phone is literally what it is. It’s a piece of metal. It probably has, like, five components in there. And out comes a wire. Even the wire is actually in some kind of steel tube. And this thing allows you to make phone calls without electricity.

So if your ship is on fire, and you need to call to the deck and say, “Hey, the ship is on fire,” this thing will actually work, unlike your voice-over-IP setup, which, after the first strike on your ship, and there’s been a power dip, and all the servers are rebooting, this thing will always work.

If you try to break it, you could probably strike it with a hammer. It will still work. It’s very difficult to disable this machine. Attempts have been made to disable it, because it’s so ridiculously simple that people think we must make progress, and we must have digital phones. And, well, this machine is still going strong. And people have tried to replace it, but in war-fighting conditions, this is the kind of machine that you need. This one can make calls to ten different stations, by the way. It’s even quite advanced. And they can make phone calls over cables that are 50 kilometers long. So it’s a very impressive machine.

And now we’re going to head to some less impressive things.

This was the Dutch Emergency Communication Network (Mini-noodnet). There is not much known about this Emergency Communication Network, although Paul might know a few things. [Paul confirms that he does] Because a lot of this stuff is sort of semi-classified, and they’re not really telling anyone about it.

But this was a copper wire network through 20 bunkers in the Netherlands, which was independent completely from the regular telephone network. It was a very simple telephone network, but it was supposed to survive war and disasters. And it had these 20 bunkers. It had guys like this guy running it. And it was fully redundant. You can see that because the top rack has B on it, and the other one has A on it. It was actually fully redundant. It was really nice stuff.

And of course, we shut it down.

Because it’s old stuff, and we need to have modern stuff. And it’s very sad. Because it has now been replaced by this:

They tried to sort of renew this emergency telephone network, but no one could do it anymore. And then they said, “Look, we’re just going to ask KPN.” And we have DSL modems, and we use the KPN VPN service. And this (the Noodcommunicatievoorziening) is now supposed to survive major incidents.

And of course, it will not.

Because every call that you make through this emergency network passes through all of KPN, like 20 different routers. And if something breaks, then this is likely the first thing that will break.

During a power outage a few years ago, there was an attempt to use the system, and it turned out that didn’t work. Because the power was out. Yeah, it’s embarrassing, but that’s what happened.

So we’ve made the trip from this wonderful thing to this pretty impressive thing to this thing. And then we have Microsoft Teams. Which is a very…

I know there are Microsoft people in the room, and I love them. When it works, it’s great. I mean, it exhausts the battery of my laptop in 20 minutes, but it’s very impressive.

And you have to realize that it works like almost always. Maybe not always audio and stuff, but quite often it will work.

So we’ve made this trip from here (sound powered phone) to here (Teams). And that’s not good. And I want to show you, (big WhatsApp logo). This is the actual Dutch government emergency network.

Which is interesting in itself, because it’s actually sort of really good at these short text-based messages. So if you want to have a modern emergency network, it could look a lot like WhatsApp. In terms of concept. Except that we should not have chosen the actual WhatsApp to do this stuff.

Because if the cable to the US is down, I can guarantee you WhatsApp is also down. So this is an emergency network that is itself not super redundant. But it’s very popular in times of disaster.

We know this because after a disaster, people do an investigation to figure out how did the communications go. And you have all these screenshots of these WhatsApp groups. So I’m not knocking it because it actually works.

Unlike this thing (the modern Voip NCV). It’s not that expensive though. They just renewed it. It’s like six million euros a year. It’s not bad.

So how bad is losing communications? The Dutch road management people (Rijkswaterstaat) have a very good Mastodon account and also a Twitter account, I assume.

Where they will almost every day tell you, look, there’s a bridge, and it won’t close. And then they say, and I find this fascinating, they say, yeah, we called the engineer. So it says here, de monteur. We called de monteur.

It is like they have one of these guys who sits there with a van, and they’re waiting for a call,

I assume they have multiple ones.

But still, you could disrupt all of the Netherlands if you just put the bridges open. So if you have any kind of war kind of situation, you’re trying to mobilize, you’re trying to get the tanks from A to B, apparently you can just shut down the bridge.

And it happens a lot. And then you need to reach the engineer. But you have to use a phone to do that. Because I assume that this engineer sits there waiting until the phone rings. And let’s say the phone does not ring, because the phone network is down, then your bridge stays open.

But also you have to find the phone number of the engineer, of course, and that might well be hiding out in an Excel sheet in your cloud environment. So that means that the effective chain to get this bridge fixed, the bridge fixed in 2024, likely includes a completely working cloud environment and a phone environment, and then hoping that the guy with the van manages to get there, and that he does not have an electric van, which also needs a cloud to drive.

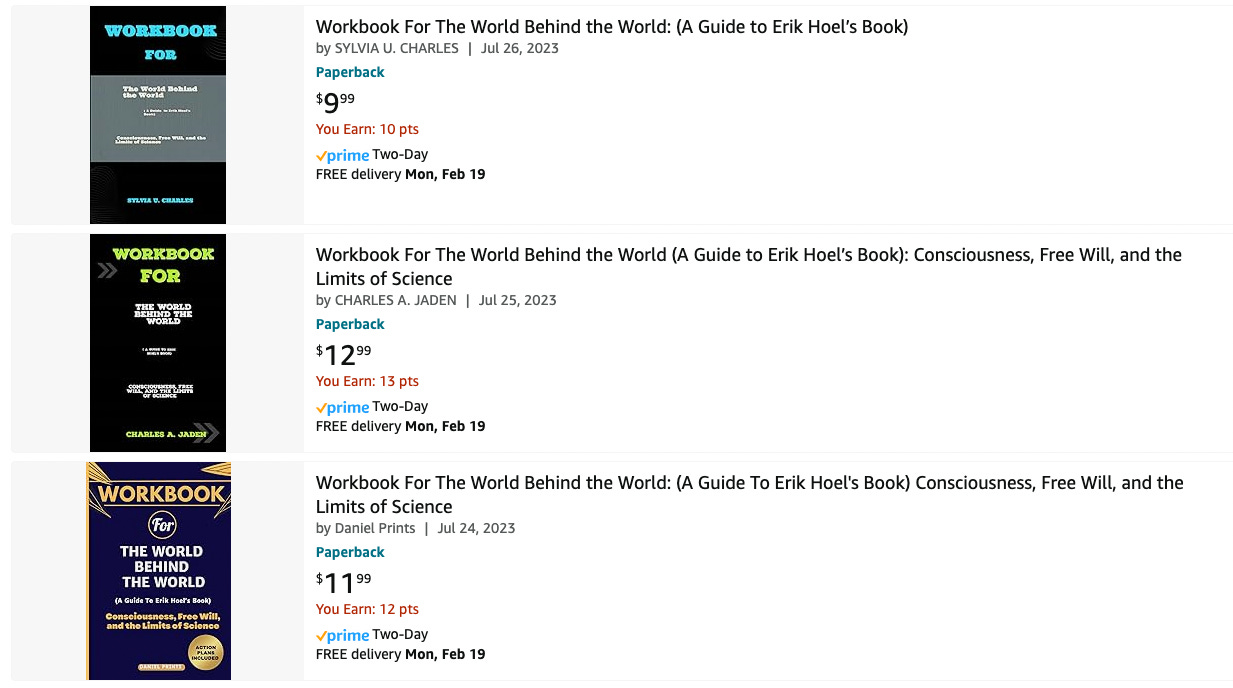

The picture on the left is, of course, well known. It’s used to illustrate that all the world of digital infrastructure often depends on just one person, which is bad enough.

But actually my thesis is this entire stack is way too high.

So if you want to run a modern society, we need all the power to be on everywhere. We need the cables to the US to be working. We need the cloud to be working. We need the phone to be working.

That’s a far cry from this lovely machine (the sound powered phone), which always works.

So I’m a bit worried that if we have panic, if we have flooding or an invasion or an attack or whatever.

I think that our infrastructure will not hold up.

I also want to mention this one. This is the Botlek Bridge. This is a modern bridge. And this bridge has failed 250 times. And in its initial years, it would fail like 75 times a year.

And when this fails, then the consequences are huge because it’s the one way that truck traffic can get from A to B. And it has failed in total hundreds of times. And for years, no one could figure out why.

So it would just block. It would no longer go up and down. And a whole task force, they took one of the engineers and they put them in a van over there. And they made them live there. They had live-in engineers here to just work on this thing if it broke. And through that work, they managed to sort of halve the downtime of this bridge.

It has its own website, this bridge, to keep track of the outages. And it has its own SMS service where it will send you text messages if it is broken (“Sms ‘BBRUG AAN’ naar 3669”, not kidding).

Because it was broken that much. Then after many years, they found out how that happened. And the story was, there is a system in there that manages the state, the sensors, and that server had a rotten ethernet cable or port.

And during that two-year period, everyone thought, it cannot be the computer. No one came and said, shall we just replace all the cables and ethernet ports for once and see what happens? We lacked the expertise.

And this is the third component I mentioned in the things that you really care about. Do you have sufficient ownership and knowledge of your own infrastructure that you can repair it?

And here, that apparently took more than three years. Maybe they just solved it by accident because someone needed that cable for their other computer.

I don’t know. But it’s super embarrassing. This is a sign that you do not have control over your own infrastructure.

That you have a major bridge and for three years long, you do not manage to find out what is wrong with it. And I worry about that.

Now it’s time for a little bit of good news. This is another big infrastructure project in the Netherlands. It’s the Maeslantkering.

And it protects us against high water. It’s a marvelous thing. It’s very near my house. Sometimes I just go there to look at it because I appreciate it so much. This machine is, again, this is the sound-powered phone infrastructure.

So you see here these two red engines that are used to push the thing close. That’s literally all they do. They only push it close. And when I visited, they said that actually, even if these engines didn’t work, they had another way of pushing it close. Because you actually need to close it when the water is really high.

And it doesn’t even need to close completely. It’s a completely passive thing. It has no sensors. So this shows that it could also be done. You can make simple infrastructure, and this is actually one of the pieces that works. They tried to mess it up by giving people some kind of weird, newly-Dutch-invented computer in here, which turned out to be bullshit. But that only takes the decision if it should close or not.

It’s a very lovely machine. So I would love to see more of this. I’d love to see more of this and less of this (Botlek bridge). Even though the pictures are marvelous.

So where are we actually with the cybersecurity? How are things going? Could we stand up to the Russian hackers? Not really.

Four years ago, we had this big discussion about 5G and if we should use Chinese infrastructure for our 5G telephony.

And everyone talking about that, politicians, thought that was a big choice that had to be made then.

And the reality was, when this decision was being taken, the Chinese were literally running all our telecommunications equipment already. But that is such an unhappy situation that people were like, “La, la, la, la, la.”

They were pretending that up to then, we were in control of our telecommunications infrastructure and we were now deciding to maybe use Chinese equipment. And that maybe that Chinese equipment could backdoor us.

But the reality was (and still partially is), they were actually running our infrastructure. If they wanted to harm us, the only thing they had to do was to stop showing up for work.

And this is still a very inconvenient truth. So I wrote this like four years ago, and it got read at the European Commission. Everyone read it. And people asked me, even very senior telco people, they said, “No, it’s not true.” And so I asked them, “So where are your maintenance people then?” So you can go to, for example, kpn.com and their job vacancies. And you will see that they never list a job vacancy that has anything to do with 5G. Because they are not running it.

And if we realized earlier that in a previous century, we had 20 bunkers with our own independent telecommunications infrastructure, because we realized that telecommunications was like really important. And now we have said, “No, it’s actually fine.” It’s being run straight from Beijing. That’s a bit of a change.

So things are not good. People want to fix this, and they are making moves to fix the situation, but we aren’t there yet.

Google, Microsoft, AWS

So these are our new overlords. This is the cloud. This is the big cloud. This is apparently, according to Dutch government and semi-government agencies, these are the only people still able to do IT.

We had a recent situtation in the Netherlands where the maintainers of .nl, and I know you’re here, decided that no one in Europe could run the IT infrastructure the way they wanted it anymore, and that they had to move it very far away.

At this point, I want to clarify, some very fine people are working here (in the cloud) I’m not saying here that these are all terrible people. I AM saying there are many thousands of kilometers away, and may not be there for us in a very bad situation.

But apparently this is the future of all our IT. And I’ve had many talks in the past few weeks on this subject, and everyone in industry is convinced that you can no longer do anything without these three companies.

And that leads to this depressing world map, where we are in the middle, and we sort of get our clouds from the left, and the people maintaining that come from the right.

And we make cheese, I think. Really good cheese. And art. And handbags. Actually, one of the biggest Dutch companies, or European companies, is a handbag company. Very excellent. Louis Vuitton. It’s apparently a Dutch company. I didn’t know that either, but for tax reasons. We’re very good at tax evasion here, by the way.

And interestingly, it’s good to look at this exciting arrow here, because we see a lot of telecommunications companies are now moving to Ericsson and Nokia equipment, which is great.

But the maintenance on your Ericsson equipment is not done by a guy called Sven.

The maintenance is actually coming from the fine people from far away. These are actually maintaining our infrastructure.

The problem is they’re very far away. The other problem is that both China, where a lot of the infrastructure actually still comes from, and India, are very closely aligned to Russia.

So we have effectively said, we’ve outsourced all our telecommunications stuff, so this is where the servers are being operated from, and these are the people that are actually maintaining the servers. And all of these places are geopolitically worrying right now, because we don’t know who wins the elections. It could be a weird guy.

And both India and China are like, “Oh, we love Russia.” How much fun would it be if our telcos were being attacked by Russian hackers, and we hope that Infosys is going to come to our rescue?

They might be busy. They could well have other important things to do.

In any other case, we are not going to save our own telecommunications companies, because we are not running them ourselves.

Oh, again, to cheer you up a little bit. This is a map of Europe, and this is within this small area. This is where all the high-tech chip-making equipment in the whole world gets made. It is not that we are completely helpless. I just said we were very good with cheese. Actually, we’re also very good with high-end optics and making chip making equipment and stuff. So it’s not that we’re completely helpless. It’s just that we’ve chosen to focus on handbags and extreme UV optics, and not running our own vital infrastructure.

So what’s the situation? Joost Schellevis, he’s a Dutch journalist, and he recently decided on a weekend to just scan the Dutch Internet to see if he could find anything broken with it. And within a weekend of work, he found 10,000 places that were just open for hackers. And this turned into a news item on the Dutch national news, and people said, “Yeah, yeah, yeah, that’s how it is.” That’s not the sort of war-like situation, that if a random journalist – and Joost is very good – but if a random journalist can just sit there in a weekend and find 10,000 places he can hack, things are not good.

I know the NCSC and other places are working on it and improving it, and they can now scan for such weaknesses. But until quite recently, journalists could scan for these things, and the Dutch government could not, because of legal reasons.

So it’s not good. The other thing I want to focus – and that’s really worrying – if we want to improve our security, it would be nice if we could tell companies, “You just need to install the right equipment. Just get good equipment, and you will be secure.” And that’s not the world we’re living in right now.

And all these places are not secure right now. So if you tell people, “Get a good firewall,” I currently have no advice for you, because all the “good ones” are actually not good. Most big security vendors right now are delivering terribly insecure products, with hundreds of issues per year.

You could not really recommend this based on just the statistics. Yet we are still doing it, because that’s the stuff that we used to buy. Again, this is a peacetime choice. In peacetime, you say, “Hey, I buy this stuff because it’s certified, because we bought it last year, and it was fine then, too.” Well, actually, it was not fine then, too, but we just – and we just keep on buying shitty stuff.

And we get away with this for now. But Ukraine does not get away with this,

And just for your calibration, we are sort of – we are no longer really impressed by it, but if you look at the weekly or monthly security updates that come to us from the big security vendors, they just go out, “Yeah, we have 441 new security problems for you this month. “And there’s Oracle, and then there’s Microsoft. “Yeah, we have 150.” And this repeats sort of every month. And I’m not going to pick on Microsoft or Oracle specifically, but it is – we’ve sort of assumed that it’s okay if you just say, “Yeah, we have 1,000 new security vulnerabilities to deal with every month from our different vendors.” We cannot have this and assume that things will be good. Yet that is what we do.

And I love this one. So you might think that, look, the hackers have become really good, really advanced. That’s why we keep finding all these security issues. And it turns out that’s not the case.

The security issues that are being found are still extremely basic. So this is, for example, help desk software that people use so that the help desk can take over your computer and stuff. And it turns out that if you connected to this appliance and you added one additional slash at the end of the URL, it would welcome you as a new administrator, allowing you to reset the password.

And this is not even – I mean, this is par for the course, because, for example, here we have GitLab, which people use to securely store their source code because they don’t want to put it on the public Internet, so they put it on their own Internet. And it has a “forgot your password” link. And it turns out that if you provide it with two email addresses and you click on “forget your password,” it will send a reset link to the second email address.

But it checked only the first email address to see if you were really the administrator. And this was in GitLab for like six months.

Many of the recent security incidents are of this level. There are, of course, very advanced attacks as well, but quite a lot of this stuff is childishly simple things.

Ivanti, if you work for the Dutch government, you will very frequently see this screen when you log in. The U.S. government has disallowed the use of this software. They have said, “You can no longer use this software.” And the Dutch government says, “Well, we put another firewall in front of it, and it’s good now.”

You can see that above in the circle. This is the elite hacking technique. Dot, dot, slash. And it still works, 2024.

So the situation is not good.

So let’s move to the cloud and fix all these things.

Again, I want to apologize to the Microsoft people because I should have diversified my hate a little bit.

Microsoft said, “Yeah, it seems that we’ve been sort of compromised, but we’re on top of it.”

And then after a while, they said, “Well, yeah, actually…”

The one fun thing, if you really want to know how it is with the security of a company, you should go to their stock exchange information because there you have to admit all your problems. And if you do not admit your problems there, the board of directors goes to jail, which makes them remarkably honest. It’s very good. If you read this from most vendors, you just cry because it’s like, “Yeah, we know. Basically everything we do is broken,” it says there. Here at the Microsoft one, Microsoft says, “Yeah, turns out when we sort of looked again, we were sort of still hacked.”

Oh, okay.

And then came the Cyber Safety Review Board in the US, which has awesome powers to investigate cyber incidents, and you really must read this report.

Microsoft is actually a member of this board, which is what makes it interesting that they were still doing a very good investigation. And they said, “Yeah, it’s actually sort of… We’re full of Chinese hackers, and we’re working on it. Work in progress.”

So if you just say, “Let’s just move to the cloud,” your life is also not suddenly secure.

That’s what I’m saying.

And meanwhile, we have decided in Europe to move everything to these clouds. The Dutch government has just managed to come up with a statement that they said that there are a few things that they will not move to the cloud. And these are the classified things and the basic government registrations.

So that’s the kind of thing that if you add something to the basic registration, you can create people.

And they said, “That’s not going to the cloud.” But basically, everything else is on the table. And we have no choice with that really anymore, because what happens, if you used to run your own applications, if you used to run your own IT infrastructure, and then you say, “We’re going to move everything to the cloud,” what happens to the people that were running your IT infrastructure? They leave. You often don’t even have to fire them, because their work gets so boring that they leave by themselves.

And that means that you end up with organizations that have started moving all the things to the cloud.

And now, if you don’t pay very close attention, you will end up with no one left that really knows what’s going on. And that means that you have to actively say:

“Okay, we know that we’re going to outsource almost everything, but we’re going to retain this limited number of staff, and we’re going to treat them really well, so that we at least, in theory, still know what is going on.”

This is not happening. So the good technical people are leaving everywhere. They actually often start working for one of these clouds, at which points they’re out of reach, because you never hear from Amazon how they do things.

This is a something we are messing up, And this is making us incredibly vulnerable, because we now have these important places that have no one left that really knows what the computer is doing.

Belle, in her opening, she mentioned, “How could you be a manager of a subject that you don’t know anything about?” And I think that it’s very good that you mentioned that, because in many other places, this is apparently not a problem.

So you could be the director of whatever cloud strategy, and you’re like, “Hey, I studied law.” And of course, it’s good that you study law, but it’s good also to realize it might be nice if you have a few people on the board that actually know what a computer does.

And this is one of the main reasons why this is happening. Our decision-making in Europe, but especially in The Netherlands, is incredibly non-technical.

So you can have a whole board full of people that studied history and art and French, and they sit there making our cloud decisions. And they simply don’t know.

And if there had been more nerds in that room, some of these things would not have happened. And that is also a call to maybe us nerds, although you don’t really look that nerdy, but do join those meetings.

Because quite often, we as technical people, we’re like, “Ah, these meetings are an interruption of my work, and I’m not joining that meeting.” And while you were not there, the company decided to outsource everything to India.

And again, there’s nothing against India, but it’s very far away.

This stuff cannot go on like this. This is a trend, a trend where we know ever less about what we are doing, where we are ever more reliant on people very far away.

The trend has already gone too far, but it’s showing no sign of stopping. It is only getting worse.

And this is my worst nightmare.

Ukraine was already at war for two years and battle-hardened. So anything that was simple to break was already broken by the Russians. Then after two years, the Russians managed to break Kyivstar, one of the biggest telecommunications companies of Ukraine, This was a very destructive attack. But the Ukrainians (in and outside Kyivstar) are good enough that in two days they were back up and running, because these people were prepared for chaos.

They knew how to restore their systems from scratch. If we get an attack like this on VodafoneZiggo or on Odido, and they don’t get external help, they will be down for half a year, because they don’t know anything about their own systems.

And I’m super worried about that, because we are sitting ducks. And we’re fine with that.

So just a reminder, when times are bad, you are much more on your own, and no one has time for you.

If something goes wrong, remember the corona crisis when we couldn’t make these personal protective equipment, these face masks.

We couldn’t make them. And we had to beg people in China if they please had time to make a few for us. Can you imagine in a war situation that we have to beg India to please, or in a different situation where we have to beg the Donald Trump administration, if they would please, please fix our cloud issues here?

It’s a worrying thought, being that dependent. And we’re not good on any of these fronts right now.

So we’re rounding off. Is there a way back? Can we fix it?

And I made a little attempt myself.

I needed to share images with people, and I did not want to use the cloud, so I wanted to have an image sharing site. And I found out that the modern image sharing site, like Imgur, is five million lines of code and complexity.

That means it’s exceptionally vulnerable, because those five million lines will have a lot of vulnerabilities.

But then I decided, I wrote my own solution, a thing of 1,600 lines of code, which is, yeah, it’s like thousands of times less than the competition.

And it works. It’s very popular. The IEEE picked it up. They even printed it in their paper magazine. I got 100 emails from people saying that it’s so nice that someone wrote a small piece of software that is robust, does not have dependencies, you know how it works.

But the depressing thing is, some of the security people in the field, they thought it was a lovely challenge to audit my 1,600 lines of code. And they were very welcome to do that, of course. And they found three major vulnerabilities in there.

Even though I know what I’m doing. I’m sort of supposed to be good at this stuff. And apparently, I was good at this stuff because I invited them to check it. And they found three major issues. And it makes me happy that you can still make this small, robust code. But it was depressing for me to see that even in 1,600 lines, you can hide three serious security vulnerabilities.

What do you think about 5 million lines? That’s basically insecure forever. So this was a little attempt to fight my way back. And at least many people agreed with me. That’s the most positive thing I can say about that.

But in summary, the systems that support our daily lives are way too complex and fragile. They fail by themselves.

So when a big telco has an outage, it is now always a question, is this a cyber thing or is it just an incompetence thing? It could both be true.

Maintenance of our technology is moving further and further away from us.

So if you look at the vacancies, the job vacancies, telecommunications companies, they’re not hiring anything, anyone that does anything with radio networks.

Our own skills are wilting. We are no longer able to control our own infrastructure. We need help from around the world to just keep the communications working.

And that is the current situation. But now imagine this in wartime, it’s all terrible.

Why did it happen? Non-technical people have made choices and have optimized for stuff being cheap. Or at least not hassle. And that’s only going to be fixed if we have more technical thinking going on.

But I have no solutions for making that happen.

And with that, I’m afraid I have no more slides to cheer you up, and I want to thank you very much for your attention.