Inside the AI Porn Marketplace Where Everything and Everyone Is for Sale

Emanuel Maiberg Aug 22, 2023

Generative AI tools have empowered amateurs and entrepreneurs to build mind-boggling amounts of non-consensual porn.

On CivitAI, a site for sharing image generating AI models, users can browse thousands of models that can produce any kind of pornographic scenario they can dream of, trained on real images of real people scraped without consent from every corner of the internet.

The “Erect Horse Penis - Concept LoRA,” an image generating AI model that instantly produces images of women with erect horse penises as their genitalia, has been downloaded 16,000 times, and has an average score of five out of five stars, despite criticism from users.

“For some reason adding ‘hands on hips’ to the prompt completely breaks this [model]. Generates just the balls with no penis 100% of the time. What a shame,” one user commented on the model. The creator of the model apologized for the error in a reply and said they hoped the problem will be solved in a future update.

The “Cock on head (the dickhead pose LoRA),” which has been downloaded 8,854 times, generates what its title describes: images of women with penises resting on their heads. The “Rest on stomach, feet up (pose)” has been downloaded 19,250 times. “these images are trained from public images from Reddit (ex. r/innie). Does not violate any [terms of service]. Pls do not remove <3,” wrote the creator of the “Realistic Vaginas - Innie Pussy 1” model, which has been downloaded more than 75,000 times. The creator of the “Instant Cumshot” model, which has been downloaded 64,502 times, said it was “Trained entirely on images of professional adult actresses, as freeze frames from 1080p+ video.”

While the practice is technically not allowed on CivitAI, the site hosts image generating AI models of specific real people, which can be combined with any of the pornographic AI models to generate non-consensual sexual images. 404 Media has seen the non-consensual sexual images these models enable on CivitAI, its Discord, and off its platform.

A 404 Media investigation shows that recent developments in AI image generators have created an explosion of communities where people share knowledge to advance this practice, for fun or profit. Foundational to the community are previously unreported but popular websites that allow anyone to generate millions of these images a month, limited only by how fast they can click their mouse, and how quickly the cloud computing solutions powering these tools can fill requests. The sheer number of people using these platforms and non-consensual sexual images they create show that the AI porn problem is far worse than has been previously reported.

Our investigation shows the current state of the non-consensual AI porn supply chain: specific Reddit communities that are being scraped for images, the platforms that monetize these AI models and images, and the open source technology that makes it possible to easily generate non-consensual sexual images of celebrities, influencers, YouTubers, and athletes. We also spoke to sex workers whose images are powering these AI generated porn without their consent who said they are terrified of how this will impact their lives.

Hany Farid, an image forensics expert and professor at University of California, Berkeley told 404 Media that it’s the same problem we’ve seen since deepfakes first appeared six years ago, only the tools for creating these images are easier to access and use.

“This means that the threat has moved from anyone with a large digital footprint, to anyone with even a modest digital footprint,” Farid Said. “And, of course, now that these tools and content are being monetized, there is even more incentive to create and distribute them.”

The Product

On Product Hunt, a site where users vote for the most exciting startups and tech products of the day, Mage, which on April 20 cracked the site’s top three products, is described as “an incredibly simple and fun platform that provides 50+ top, custom Text-to-Image AI models as well as Text-to-GIF for consumers to create personalized content.”

“Create anything,” Mage.Space’s landing page invites users with a text box underneath. Type in the name of a major celebrity, and Mage will generate their image using Stable Diffusion, an open source, text-to-image machine learning model. Type in the name of the same celebrity plus the word “nude” or a specific sex act, and Mage will generate a blurred image and prompt you to upgrade to a “Basic” account for $4 a month, or a “Pro Plan” for $15 a month. “NSFW content is only available to premium members.” the prompt says.

To get an idea of what kind of explicit images you can generate with a premium Mage subscription, click over to the “Explore” tab at the top of the page and type in the same names and terms to search for similar images previously created by other users. On first impression, the Explore page makes Mage seem like a boring AI image generating site, presenting visitors with a wall of futuristic cityscapes, cyborgs, and aliens. But search for porn with “NSFW” content enabled and Mage will reply with a wall of relevant images. Clicking on any one of them will show when they were created, with what modified Stable Diffusion model, the text prompt that generated the image, and the user who created it.

Since Mage by default saves every image generated on the site, clicking on a username will reveal their entire image generation history, another wall of images that often includes hundreds or thousands of AI-generated sexual images of various celebrities made by just one of Mage’s many users. A user’s image generation history is presented in reverse chronological order, revealing how their experimentation with the technology evolves over time.

Scrolling through a user’s image generation history feels like an unvarnished peek into their id. In one user’s feed, I saw eight images of the cartoon character from the children's’ show Ben 10, Gwen Tennyson, in a revealing maid’s uniform. Then, nine images of her making the “ahegao” face in front of an erect penis. Then more than a dozen images of her in bed, in pajamas, with very large breasts. Earlier the same day, that user generated dozens of innocuous images of various female celebrities in the style of red carpet or fashion magazine photos. Scrolling down further, I can see the user fixate on specific celebrities and fictional characters, Disney princesses, anime characters, and actresses, each rotated through a series of images posing them in lingerie, schoolgirl uniforms, and hardcore pornography. Each image represents a fraction of a penny in profit to the person who created the custom Stable Diffusion model that generated it.

Mage displays the prompt the user wrote in order to generate the image to allow other users to iterate and improve upon images they like. Each of these reads like an extremely horny and angry man yelling their basest desires at Pornhub’s search function. One such prompt reads:

"[[[narrow close-up of a dick rubbed by middle age VERY LUSTFUL woman using her MOUTH TO PLEASURE A MAN, SPERM SPLASH]]] (((licking the glans of BIG DICK))) (((BLOWjob, ORAL SEX))) petting happy ending cumshot (((massive jizz cum))))(((frame with a girl and a man)))) breeding ((hot bodies)) dribble down his hard pumping in thick strokes, straight sex, massage, romantic, erotic, orgasm porn (((perfect ball scrotum and penis with visible shaft and glans))) [FULL BODY MAN WITH (((woman face mix of Lisa Ann+meghan markle+brandi love moaning face, sweaty, FREKLESS, VERY LONG BRAID AND FRINGE, brunette HAIR)), (man Mick Blue face)"

This user, who shares AI-generated porn almost exclusively, has created more than 16,000 images since January 13. Another user whose image history is mostly pornographic generated more than 6,500 images since they started using Mage on January 15, 2023.

On the official Mage Discord, which has more than 3,000 members, and where the platform’s founders post regularly, users can choose from dozens of chat rooms organized by categories like “gif-nsfw,” “furry-nsfw,” “soft-women-nsfw,” and share tricks on how to create better images.

“To discover new things I often like to find pictures from other users I like and click remix. I run it once and add it to a list on my profile called ‘others prompts’ then I'll use that prompt as a jumping off point,” one user wrote on July 12. “It's a good way to try different styles as you hone your own style.”

“anyone have any luck getting an [sic] good result for a titty-fuck?” another user asked July 17, prompting a couple of other users to share images of their attempts.

Generating pornographic images of real people is against the Mage Discord community’s rules, which the community strictly enforces because it’s also against Discord’s platform-wide community guidelines. A previous Mage Discord was suspended in March for this reason. While 404 Media has seen multiple instances of non-consensual images of real people and methods for creating them, the Discord community self-polices: users flag such content, and it’s removed quickly. As one Mage user chided another after they shared an AI-generated nude image of Jennifer Lawrence: “posting celeb-related content is forbidden by discord and our discord was shut down a few weeks ago because of celeb content, check [the rules.] you can create it on mage, but not share it here.”

Gregory Hunkins and Roi Lee, Mage’s founders, told me that Mage has over 500,000 accounts, a million unique creators active on it every month, and that the site generates a “seven-figure” annual revenue. More than 500 million images have been generated on the site so far, they said.

“To be clear, while we support freedom of expression, NSFW content constitutes a minority of content created on our platform,” Lee and Hunkins said in a written statement. “NSFW content is behind a paywall to guard against those who abuse the Mage Space platform and create content that does not abide by our Terms & Conditions. One of the most effective guards against anonymity, repeat offenders, and enforcing a social contract is our financial institutions.”

When asked about the site’s moderation policies, Lee and Hunkins explained that Mage uses an automated moderation system called “GIGACOP” that warns users and rejects prompts that are likely to be abused. 404 Media did not encounter any such warning in its testing, and Lee and Hunkins did not respond to a question about how exactly GIGACOP works. They also said that there are “automated scans of the platform to determine if patterns of abuse are evading our active moderation tools. Potential patterns of abuse are then elevated for review by our moderation team.”

However, 404 Media found that on Mage’s site AI-generated non-consensual sexual images are easy to find and are functionally infinite.

“The scale of Mage Space and the volume of content generated antiquates previous moderation strategies, and we are continuously working to improve this system to provide a safe platform for all,” Lee and Hunkins said. “The philosophy of Mage Space is to enable and empower creative freedom of expression within broadly accepted societal boundaries. This tension and balance is a very active conversation right now, one we are excited and proud to be a part of. As the conversation progresses, so will we, and we welcome all feedback.”

Laura Mesa, Product Hunt’s vice president of marketing and community, told me that Mage violates Product Hunt’s policy, and Mage was removed shortly after I reached out for comment.

The images Mage generates are defined by the technology it’s allowing users to access. Like many of the smaller image generating AI tools online, at its core it’s powered by Stable Diffusion, which surged in popularity when it was released last year under the Creative ML OpenRAIL-M license, allowing users to modify it for commercial and non-commercial purposes.

Mage users can choose what kind of “base model” they want to use to generate their images. These base models are modified versions of Stable Diffusion that have been trained to produce a particular type of image. The “Anime Pastel Dream” model, for example, is great at producing images that look like stills from big budget anime, while “Analog Diffusion” is good at giving images a vintage film photo aesthetic.

One of the most popular base models on Mage is called “URPM,” an acronym for “Uber Realistic Porn Merge.” That Stable Diffusion model, as well as others designed to produce pornography, are created upstream in the AI porn supply chain, where people train AI to recreate the likeness of anyone, doing anything.

The People Who Become Datasets

Generative AI tools like Stable Diffusion use a deep learning neural network that was trained on a massive dataset of images. This dataset then generates new images by predicting how pixels should be arranged based on patterns in the dataset and what kind of image the prompt is asking for. For example, LAION-5B, an open source dataset made up of over 5 billion images scraped from the internet, helps power Stable Diffusion.

This makes Stable Diffusion good at generating images of broad concepts, but not specific people or esoteric concepts (like women with erect horse penises). But because Stable Diffusion code is public, over the last year researchers and anonymous users have come up with several ingenious ways to train Stable Diffusion to generate such images with startling accuracy.

In August of 2022, researchers from Tel Aviv University introduced the concept of “textual inversion.” This method trains Stable Diffusion on a new “concept,” which can be an object, person, texture, style, or composition, with as few as 3-5 images, and be represented by a specific word or letter. Users can train Stable Diffusion on these new concepts without retraining the entire Stable Diffusion model, which would be “prohibitively expensive,” as the researchers explain in their paper.

In their paper, the researchers demonstrated their method by training the image generator on a few images of a Furby, represented by the letter S. They can then give the image generator the prompt “A mosaic depicting S,” or “An artist drawing S,” and get the following results:

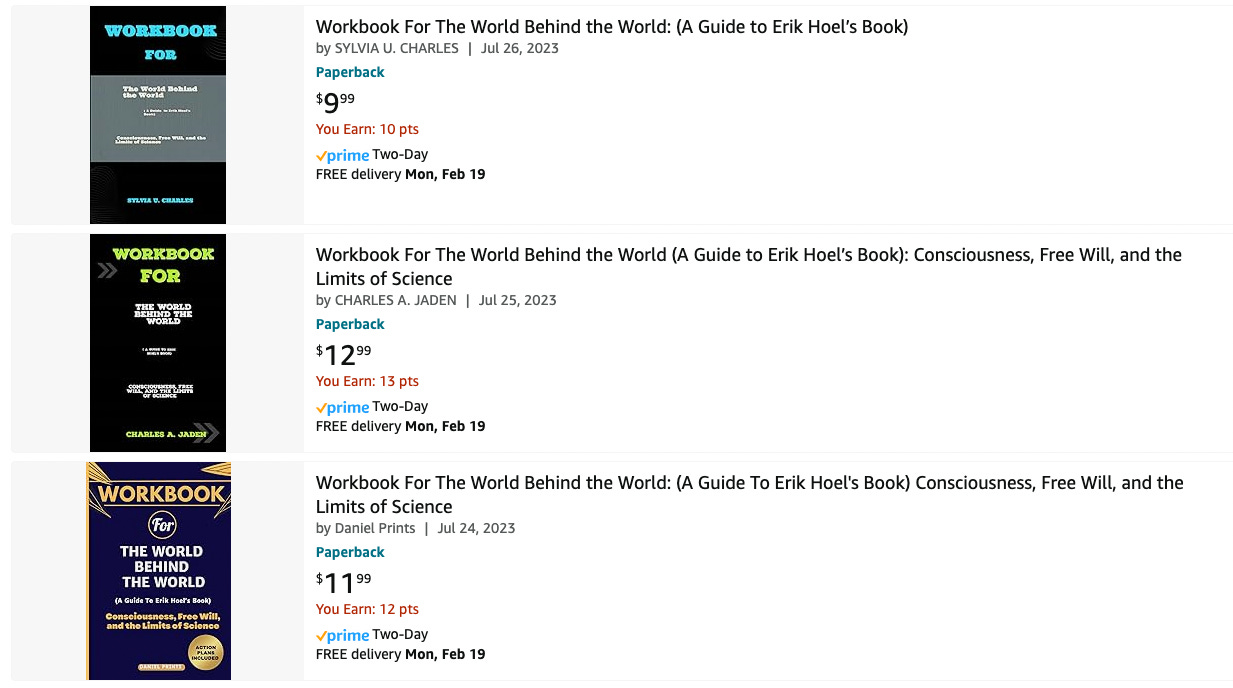

By September 2022, AUTOMATIC1111, a Github user who maintains a popular web interface for Stable Diffusion, explained how to implement textual inversion. In November, a web developer named Justin Maier launched CivitAI, a platform where people could easily share the specific models they’ve trained using textual inversion and similar methods, so other users could download them, generate similar images, iterate on the models by following countless YouTube tutorials, and combine them with other models trained on other specific concepts.

There are many non-explicit models on CivitAI. Some replicate the style of anime, popular role-playing games, or Chinese comic books. But if you sort CivitAI’s platform by the most popular models, they are dominated by models that expertly produce pornography.

LazyMix+ (Real Amateur Nudes), for example, produces very convincing nudes that look like they were shot by an amateur OnlyFans creator or an image from one of the many subreddits where people share amateur porn. Many Stable Diffusion models on CivitAI don’t say what data they were trained on, and others are just tweaking and combining other, already existing models. But with LazyMix+ (Real Amateur Nudes), which has been downloaded more than 71,000 times, we can follow the trail to the source.

According to the model’s description, it’s a merge between the original LazyMix model and a model called Subreddit V3, the latter of which states it was trained on images from a variety of adult-themed subreddit communities like r/gonewild, famously where average Reddit users post nudes, r/nsfw, r/cumsluts and 38 other subreddits.

“There's nothing that's been done in the past to protect us so I don't see why this would inspire anyone to make protections against it.”

A Reddit user who goes by Pissmittens and moderates r/gonewild, r/milf, and several other big adult communities said he suspects that most people who post nudes to these subreddits probably don’t know their images are being used to power AI models.

“The issue many of them run into is that usually places misusing their content aren’t hosted in the United States, so DMCA is useless,” Pissmittens said, referring to copyright law. “The problem, obviously, is that there doesn’t seem to be any way for them to know if their content has been used to generate [computer generated] images.”

Fiona Mae, who promotes her OnlyFans account on several subreddits including some of those scraped by Subreddit V3, told me that the fact that anyone can type a body type and sex act into an AI generator and instantly get an image “terrifies” her.

“Sex workers and femmes are already dehumanized,” she said. “Literally having a non-human archetype of a woman replacing jobs and satisfying a depiction of who women should be to men? I only see that leading more to serving the argument that femmes aren’t human.”

“I have no issue with computer generated pornography at all,” GoAskAlex, an adult performer who promotes her work on Reddit, told me. “My concern is that adult performers are ultimately unable to consent to their likeness being artificially reproduced.”

An erotic artist and performer who goes by sbdolphin and promotes her work on Reddit told me that this technology could be extremely dangerous for sex workers.

“There's nothing that's been done in the past to protect us so I don't see why this would inspire anyone to make protections against it,” she said.

404 Media has also found multiple instances of non-consensual sexual imagery of specific people hosted on CivitAI. The site allows pornography, and it allows people to use AI to generate images of real people, but does not allow users to share images that do both things at once. Its terms of service say it will remove “content depicting or intended to depict real individuals or minors (under 18) in a mature context.” While 404 Media has seen CivitAI enforce this policy and remove such content multiple times, non-consensual sexual imagery is still posted to the site regularly, and in some cases has stayed online for months.

When looking at a Stable Diffusion model on CivitAI, the site will populate its page with a gallery of images other users have created using the same model. When 404 Media viewed a Billie Eilish model, CivitAI populated the page’s gallery with a series of images from one person who used the model to generate nude images of a pregnant Eilish.

That gallery was in place for weeks, but has since been removed. The user who created the nude images is still active on the site. The Billie Eilish model is also still hosted on CivitAI, and its gallery doesn’t include any fully nude images of Eilish, but it did include images of her in lingerie and very large breasts, which is also against CivitAI’s terms of service and were eventually removed.

The Ares Mix model, which has been downloaded more than 32,000 times since it was uploaded to CivitAI in February, is described by its creator as being good for generating images of “nude photographs on different backgrounds and some light hardcore capabilities.” The gallery at the bottom of the model’s page mostly showcases “safe for work” images of celebrities and pornographic images of seemingly computer-generated people, but it also includes an AI-generated nude image of the actress Daisy Ridley. Unlike the Billie Eilish example, the image is not clearly labeled with Ridley’s name, but the generated image is convincing enough that she’s recognizable on sight.

Clicking on the image also reveals the prompt used to generate the image, which starts: “(((a petite 19 year old naked girl (emb-daisy) wearing, a leather belt, sitting on floor, wide spread legs))).”

The nude image was created by merging the Ares Mix model with another model hosted on CivitAI dedicated to generating the actress’s likeness. According to that model’s page, its “trigger words” (in the same way “S” triggered the Furby in the textual inversion scientific paper) are “emb-daisy.” Like many of the Stable Diffusion models of real people hosted on CivitAI, it includes the following message:

“This resource is intended to reproduce the likeness of a real person. Out of respect for this individual and in accordance with our Content Rules, only work-safe images and non-commercial use is permitted.”

CivitAI’s failure to moderate Ridley’s image shows the abuse CivitAI facilitates despite its official policy. Models that generate pornographic images are allowed. Models that generate images of real people are allowed. Combining the two is not. But there’s nothing preventing people from putting the pieces together, generating non-consensual sexual images, and sharing them off CivitAI’s platform.

“In general, the policies sound difficult to enforce,” Tiffany Li, a law professor at the University of San Francisco School of Law and an expert on privacy, artificial intelligence, and technology platform governance, told 404 Media. “It appears the company is trying, and there are references to concepts like consent, but it's all a bit murky.”

This makes the countless models of real people hosted on CivitAI terrifying. Every major actor you can think of has a Stable Diffusion model on the site. So do countless Instagram influencers, YouTubers, adult film performers, and athletes.

“As these systems are deployed and it becomes the norm to generate and distribute pornographic images of ordinary people, the people who end up being negatively impacted are people at the bottom of society.”

404 Media has seen at least two Stable Diffusion models of Nicole Sanchez, a Twitch streamer and TikTok personality better known as Neekolul or the “OK boomer girl,” hosted on CivitAI, each of which was downloaded almost 500 times. While we didn’t see any non-consensual sexual images we could verify were created with those models, Sanchez told 404 Media that she has seen pornographic AI-generated images of herself online.

“I don't like it at all and it feels so gross knowing people with a clear mind are doing this to creators who likely wouldn't want this to be happening to them. Since this is all very new, I’m hoping that there will be clearer ethical guidelines around it and that websites will start implementing policies against NSFW content, at least while we learn to live alongside AI,” Sanchez said. “So until then, I hope that websites used to sell this content will put guidelines in place to protect people from being exploited because it can be extremely damaging to their mental health.”

Saftle, the CivitAI user who created Uber Realistic Porn Merge (URPM), one of the most popular models on the site that is also integrated with Mage, said that CivitAI is “thankfully” one of the only platforms actively trying to innovate and block out this type of content. “However it's probably a constant struggle due to people trying to outsmart their current algorithms and bots,” he said.

Li said that while these types of non-consensual sexual images are not new, there is still no good way for victims to combat them.

“At least in some states, they can sue the people who created AI-generated intimate images of them without their consent. (Even in states without these laws, there may be other legal methods to do it.) But it can be hard to find the makers of the images,” Li said. “They may be using these AI-generating sites anonymously. They may even have taken steps to shield their digital identity. Some sites will not give up user info without a warrant.”

“As these systems are deployed and it becomes the norm to generate and distribute pornographic images of ordinary people, the people who end up being negatively impacted are people at the bottom of society,” Abeba Birhane, a senior fellow in Trustworthy AI at Mozilla Foundation and lecturer at the School of Computer Science and Statistics at Trinity College Dublin, Ireland, told 404 Media. “It always ends up negatively impacting those that are not able to defend themselves or those who are disfranchised. And these are the points that are often left out in the debate of technicality.”

The Money

The creators of these models offer them for free, but accept donations. Saftle had 120 paying Patreon members to support his project before he “paused” his Patreon in May when he got a full time job. He told me that he made $1,500 a month from Patreon at its peak. He also said that while he has no formal relationship with Mage Space, he did join its “creators program,” which paid him $0.001 for every image that was generated on the site using URPM. He said he made about $2,000-$3,000 a month (equal to 2-3 million images) when he took part in the program, but has since opted out. Lee and Hunkins, Mage’s founders, told me that “many model creators earn well in excess of this,” but not all models on Mage specialize in sexual images.

The creator of “Rest on stomach, feet up (pose)” links to their Ko-Fi account, where people can send tips. One CivitAI user, who created dozens of models of real people and models that generate sexual images, shares their Bitcoin wallet address in their profile. Some creators will do all the work for you for a price on Fiverr.

Clicking the “Run Model” button at the top of every model page will bring up a window that sends users to a variety of sites and services that can generate images with that model, like Mage Space, or Dazzle.AI, which charges $0.1 per image.

CivitAI itself also collects donations, and offers a $5 a month membership that gives users early access to new features and unique badges for their usernames on the site and Discord.

“Civitai exists to democratize AI media creation, making it a shared, inclusive, and empowering journey.” CivitAI’s site says.

Justin Maier, CivitAI’s founder, did not respond to a request for comment via LinkedIn, Twitter, Discord, and email.

The Singularity

Since ChatGPT, DALL-E, and other generative AI tools became available on the internet, computer scientists, ethicists, and politicians have been increasingly discussing “the singularity,” a concept that until recently existed mostly in the realm of science fiction. It describes a hypothetical point in the future when AI becomes so advanced, it triggers an uncontrollable explosion of technological development that quickly surpasses and supersedes humanity.

As many experts and journalists have observed, there is no evidence that companies like OpenAI, Facebook, and Google have created anything even close to resembling an artificial general intelligence agent that could bring about this technological apocalypse, and promoting that alarmist speculation serves their financial interests because it makes their AI tools seem more powerful and valuable than they actually are.

However, it’s a good way to describe the massive changes that have already taken hold in the generative AI porn scene. An AI porn singularity has already occurred, an explosion of non-consensual sexual imagery that’s seeping out of every crack of internet infrastructure if you only care to look, and we’re all caught up in it. Celebrities big and small and normal people. Images of our faces and bodies are fueling a new type of pornography in which humans are only a memory that’s copied and remixed to instantly generate whatever sexual image a user can describe with words.

Samantha Cole contributed reporting.