Here lies the internet, murdered by generative AIhttps://www.theintrinsicperspective.com/p/here-lies-the-internet-murdered-by

Here lies the internet, murdered by generative AI

Corruption everywhere, even in YouTube's kids content

Erik Hoel Feb 27, 2024

Art for The Intrinsic Perspective is by Alexander Naughton

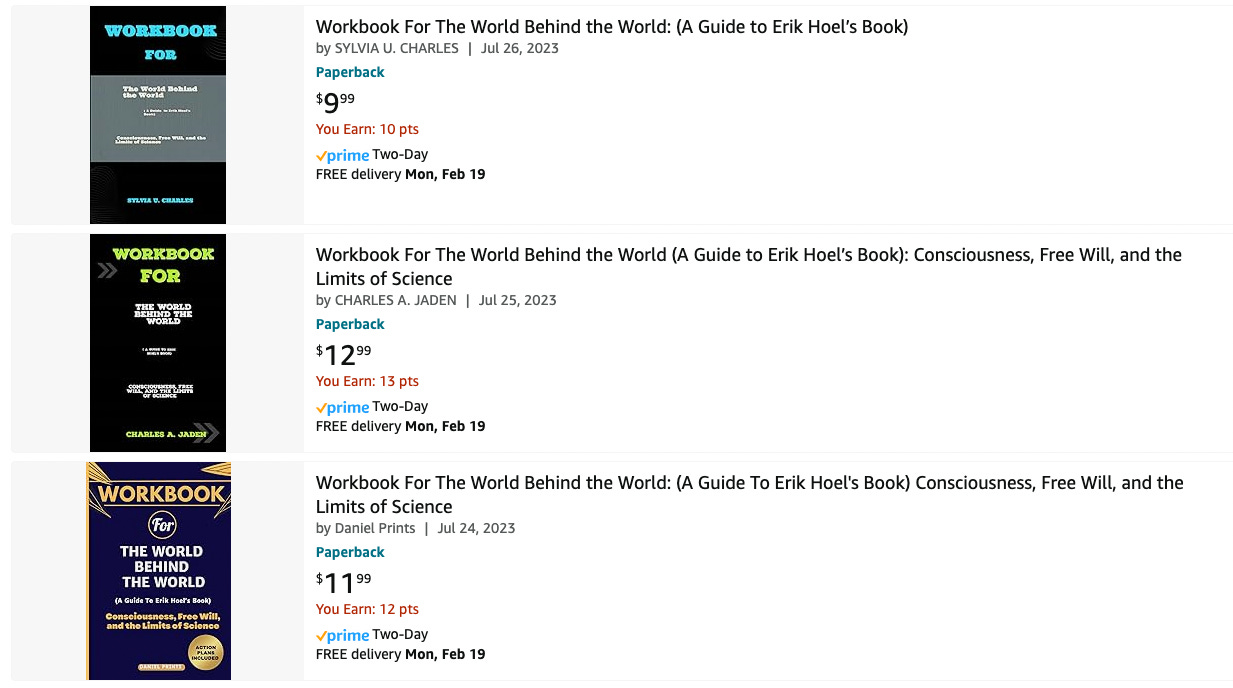

The amount of AI-generated content is beginning to overwhelm the internet. Or maybe a better term is pollute. Pollute its searches, its pages, its feeds, everywhere you look. I’ve been predicting that generative AI would have pernicious effects on our culture since 2019, but now everyone can feel it. Back then I called it the coming “semantic apocalypse.” Well, the semantic apocalypse is here, and you’re being affected by it, even if you don’t know it. A minor personal example: last year I published a nonfiction book, The World Behind the World, and now on Amazon I find this.

What, exactly, are these “workbooks” for my book? AI pollution. Synthetic trash heaps floating in the online ocean. The authors aren’t real people, some asshole just fed the manuscript into an AI and didn’t check when it spit out nonsensical summaries. But it doesn’t matter, does it? A poor sod will click on the $9.99 purchase one day, and that’s all that’s needed for this scam to be profitable since the process is now entirely automatable and costs only a few cents. Pretty much all published authors are affected by similar scams, or will be soon.

Now that generative AI has dropped the cost of producing bullshit to near zero, we see clearly the future of the internet: a garbage dump. Google search? They often lead with fake AI-generated images amid the real things. Post on Twitter? Get replies from bots selling porn. But that’s just the obvious stuff. Look closely at the replies to any trending tweet and you’ll find dozens of AI-written summaries in response, cheery Wikipedia-style repeats of the original post, all just to farm engagement. AI models on Instagram accumulate hundreds of thousands of subscribers and people openly shill their services for creating them. AI musicians fill up YouTube and Spotify. Scientific papers are being AI-generated. AI images mix into historical research. This isn’t mentioning the personal impact too: from now on, every single woman who is a public figure will have to deal with the fact that deepfake porn of her is likely to be made. That’s insane.

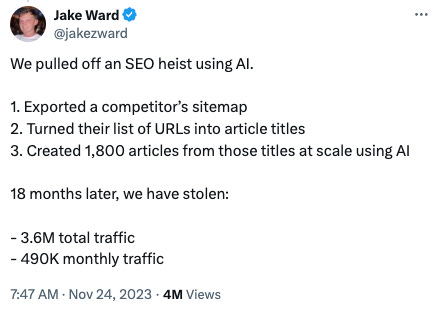

And rather than this being pure skullduggery, people and institutions are willing to embrace low-quality AI-generated content, trying to shift the Overton window to make things like this acceptable:

That’s not hardball capitalism. That’s polluting our culture for your own minor profit. It’s not morally legitimate for the exact same reasons that polluting a river for a competitive edge is not legitimate. Yet name-brand media outlets are embracing generative AI just like SEO-spammers are, for the same reasons.

E.g., investigative work at Futurism caught Sports Illustrated red-handed using AI-generated articles written by fake writers. Meet Drew Ortiz.

He doesn’t exist. That face is an AI-generated portrait, which was previously listed for sale on a website. As Futurism describes:

Ortiz isn't the only AI-generated author published by Sports Illustrated, according to a person involved with the creation of the content…

"At the bottom [of the page] there would be a photo of a person and some fake description of them like, 'oh, John lives in Houston, Texas. He loves yard games and hanging out with his dog, Sam.' Stuff like that," they continued. "It's just crazy."

This isn’t what everyone feared, which is AI replacing humans by being better—it’s replacing them because AI is so much cheaper. Sports Illustrated was not producing human-quality level content with these methods, but it was still profitable.

The AI authors' writing often sounds like it was written by an alien; one Ortiz article, for instance, warns that volleyball "can be a little tricky to get into, especially without an actual ball to practice with."

Sports Illustrated, in a classy move, deleted all the evidence. Drew was replace by Sora Tanaka, bearing a face also listed for sale on the same website with the description of a “joyful asian young-adult female with long brown hair and brown eyes.”

Given that even prestigious outlets like The Guardian refuse to put any clear limits on their use of AI, if you notice odd turns of phrase or low-quality articles, the likelihood that they’re written by an AI, or with AI-assistance, is now high.

Sadly, the people affected the most by generative AI are the ones who can’t defend themselves. Because they don’t even know what AI is. Yet we’ve abandoned them to swim in polluted information currents. I’m talking, unfortunately, about toddlers. Because let me introduce you to…

the hell that is AI-generated children’s YouTube content.

YouTube for kids is quickly becoming a stream of synthetic content. Much of it now consists of wooden digital characters interacting in short nonsensical clips without continuity or purpose. Toddlers are forced to sit and watch this runoff because no one is paying attention. And the toddlers themselves can’t discern that characters come and go and that the plots don’t make sense and that it’s all just incoherent dream-slop. The titles don’t match the actual content, and titles that are all the parents likely check, because they grew up in a culture where if a YouTube video said BABY LEARNING VIDEOS and had a million views it was likely okay. Now, some of the nonsense AI-generated videos aimed at toddlers have tens of millions of views.

Here’s a behind-the-scenes video on a single channel that made 1.2 million dollars via AI-generated “educational content” aimed at toddlers.

As the video says:

These kids, when they watch these kind of videos, they watch them over and over and over again.

They aren’t confessing. They’re bragging. And the particular channel they focus on isn’t even the worst offender—at least that channel’s content mostly matches the subheadings and titles, even if the videos are jerky, strange, off-putting, repetitious, clearly inhuman. Other channels, which are also obviously AI-generated, get worse and worse. Here’s a “kid’s education” channel that is AI-generated (took about one minute to find) with 11.7 million subscribers.

They don’t use proper English, and after quickly going through some shapes like the initial video title promises (albeit doing it in a way that makes you feel like you’re going insane) the rest of the video devolves into randomly-generated rote tasks, eerie interactions, more incorrect grammar, and uncanny musical interludes of songs that serve no purpose but to pad the time. It is the creation of an alien mind.

Here’s an example of the next frontier: completely start-to-finish AI-generated music videos for toddlers. Below is a how-to video for these new techniques. The result? Nightmarish parrots with twisted double-beaks and four mutated eyes singing artificial howls from beyond. Click and behold (or don’t, if you want to sleep tonight).

All around the nation there are toddlers plunked down in front of iPads being subjected to synthetic runoff, deprived of human contact even in the media they consume. There’s no other word but dystopian. Might not actual human-generated cultural content normally contain cognitive micro-nutrients (like cohesive plots and sentences, detailed complexity, reasons for transitions, an overall gestalt, etc) that the human mind actually needs? We’re conducting this experiment live. For the first time in history developing brains are being fed choppy low-grade and cheaply-produced synthetic data created en masse by generative AI, instead of being fed with real human culture. No one knows the effects, and no one appears to care. Especially not the companies, because…

OpenAI has happily allowed pollution.

Why blame them, specifically? Well, first of all, their massive impact—e.g., most of the kids videos are built from scripts generated by ChatGPT. And more generally, what AI capabilities are considered okay to deploy has long been a standard set by OpenAI. Despite their supposed safety focus, OpenAI failed to foresee that its creations would thoroughly pollute the internet across all platforms and services. You can see this failure in how they assessed potential negative outcomes in the announcement of GPT-2 on their blog, back in 2019. While they did warn that these models could have serious longterm consequences for the information ecosystem, the specifics they were concerned with were things like:

Generate misleading news articles

Impersonate others online

Automate the production of abusive or faked content to post on social media

Automate the production of spam/phishing content

This may sound kind of in line with what’s happened, but if you read further, it becomes clear that what they meant by “faked content” was mainly malicious actors promoting misinformation, or the same shadowy malicious actors using AI to phish for passwords, etc.

These turned out to be only minor concerns compared to AI’s cultural pollution. OpenAI kept talking about “actors” when they should have been talking about “users.” Because it turns out, all AI-generated content is fake! Or it’s all kind of fake. AI-written websites, now sprouting up like an unstoppable invasive species, don’t necessarily have an intent to mislead; it’s just that AI content is low-effort banalities generated for pennies, so you can SEO spam and do all sorts of manipulative games around search to attract eyeballs and ad revenue.

That is, the OpenAI team didn’t stop to think that regular users just generating mounds of AI-generated content on the internet would have very similar negative effects to as if there were a lot of malicious use by intentional bad actors. Because there’s no clear distinction! The fact that OpenAI was both honestly worried about negative effects, and at the same time didn’t predict the enshittification of the internet they spearheaded, should make us extremely worried they will continue to miss the negative downstream effects of their increasingly intelligent models. They failed to foresee the floating mounds of clickbait garbage, the synthetic info-trash cities, all to collect clicks and eyeballs—even from innocent children who don’t know any better. And they won’t do anything to stop it, because…

AI pollution is a tragedy of the commons.

This term, "tragedy of the commons,” originated in the rising environmentalism of the 20th century, and would lead to many of the regulations that keep our cities free of smog and our rivers clean. Garrett Hardin, an ecologist and biologist, coined it in an article in [Science](https://math.uchicago.edu/~shmuel/Modeling/Hardin, Tragedy of the Commons.pdf) in 1968. The article is still instructively relevant. Hardin wrote:

An implicit and almost universal assumption of discussions published in professional and semipopular scientific journals is that the problem under discussion has a technical solution…

He goes on to discuss several problems for which there are no technical solutions, since rational actors will drive the system toward destruction via competition:

The tragedy of the commons develops in this way. Picture a pasture open to all. It is to be expected that each herdsman will try to keep as many cattle as possible on the commons. Such an arrangement may work reasonably satisfactorily for centuries because tribal wars, poaching, and disease keep the numbers of both man and beast well below the carrying capacity of the land. Finally, however, comes the day of reckoning, that is, the day when the long-desired goal of social stability becomes a reality. At this point, the inherent logic of the commons remorselessly generates tragedy.

One central example of Hardin’s became instrumental to the environmental movement.

… the tragedy of the commons reappears in problems of pollution. Here it is not a question of taking something out of the commons, but of putting something in—sewage, or chemical, radioactive, and heat wastes into water; noxious and dangerous fumes into the air; and distracting and unpleasant advertising signs into the line of sight. The calculations of utility are much the same as before. The rational man finds that his share of the cost of the wastes he discharges into the commons is less than the cost of purifying his wastes before releasing them. Since this is true for everyone, we are locked into a system of "fouling our own nest," so long as we behave only as independent, rational, free-enterprisers.

We are currently fouling our own nests. Since the internet economy runs on eyeballs and clicks the new ability of anyone, anywhere, to easily generate infinite low-quality content via AI is now remorselessly generating tragedy.

The solution, as Hardin noted, isn’t technical. You can’t detect AI outputs reliably anyway (another initial promise that OpenAI abandoned). The companies won’t self regulate, given their massive financial incentives. We need the equivalent of a Clean Air Act: a Clean Internet Act. We can’t just sit by and let human culture end up buried.

Luckily we’re on the cusp of all that incredibly futuristic technology promised by AI. Any day now, our GDP will start to rocket forward. In fact, soon we’ll cure all disease, even aging itself, and have robot butlers and Universal Basic Income and high-definition personalized entertainment. Who cares if toddlers had to watch inhuman runoff for a few billion years of viewing-time to make the future happen? It was all worth it. Right? Let’s wait a little bit longer. If we wait just a little longer utopia will surely come.